Quick Search

Think You or a Loved One Has an Undiagnosed Rare Disease?

If you think you or someone you care for may have an undiagnosed rare disease, here are some steps you can take.

Getting a timely and accurate diagnosis can be a challenge for people living with a rare disease.

- It can take 5-7 to years, sometimes longer for people to get a diagnosis

- 4 out of 10 people living with rare disease in Australia report seeing more than 6 doctors and having at least 1 misdiagnosis1

This resource provides some steps you can take if you think you, or someone you care for, has an undiagnosed rare disease.

Step 1: Talk to Your General Practitioner or Specialist Doctor About the Symptoms You Are Experiencing

It may be helpful to keep a symptom diary to prepare for your appointment. This can help with recognising symptoms that may indicate your symptoms are due to a rare disease. You can download a simple template to use as a guide from Coping Together’s website.

Step 2: Discuss a Potential Rare Disease Diagnosis Plan or Strategy With Your Doctor

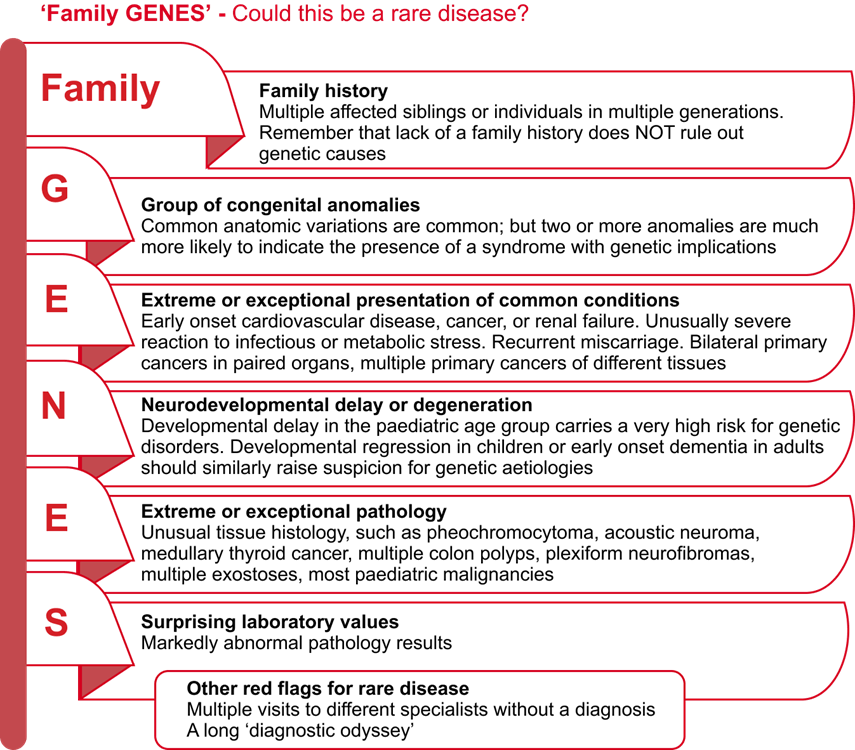

The National Recommendations for Rare Disease Health Care includes recommendations to help with a rare disease diagnosis. See Recommendation 2. The simple Family GENES ‘red flags’ tool may be helpful for your doctor. This tool was designed to help doctors in particular think about when genetic testing may be helpful, given about 80% of rare diseases have an underlying genetic cause. 2

Family GENES tool. Adapted from the Genetics in Primary Care Faculty Development Initiative.3

If you are experiencing red flags for a rare genetic disease your doctor may suggest a referral to a clinical genetics service. This Information on Genetic Services page provides more information about finding clinical genetics services. It also links to resources about genetic testing and things to think about if a genetic test has been suggested. Most public clinical genetics services have a referral information line for doctors. This can help to make sure the referral is suitable and has all the relevant information. Public clinical genetics services are free of charge but may have a long waiting list. There are also a growing number of private clinical genetics services, many of which use telehealth.

Step 3: Ask About Other Tests and Referrals

If your child is not meeting milestones or has stopped doing something they previously did like talking, your general practitioner (GP) or paediatrician can order certain types of Medicare subsidised chromosomal tests. If these tests do not provide any answers, a referral to a developmental paediatrician for Medicare subsidised genetic testing may be suitable.

FaceMatch is a free tool that may help people who suspect they, or their child, could have a genetic disease. The tool tries to find a diagnosis by studying and matching facial features and comparing them to people who already have a diagnosis. If a potential match is found, FaceMatch can also help to connect you with medical experts for further guidance. The website explains the entire process.

Step 4: Have Follow Up Discussions with Your General Practitioner

Discuss with your GP if other referrals may be more suitable for your combination of symptoms. In this case, a referral to an appropriate specialist doctor, such as a neurologist, for example, should be considered for further investigation.

What Should I Do If I Have Tried These Things and Still Have No Answers?

Getting answers can be difficult. “It is estimated that a diagnosis explaining all symptoms cannot be made for at least half the people assessed by health professionals as being likely to have a rare disease.”2

Talk to Your General Practitioner Again About the Next Best Steps

Remember, if you or your child have had a genetic test in the past that did not provide any answers, these tests are continually improving. So, a referral back to a clinical genetics service may be most appropriate, especially if it was more than 18 months to 2 years since your last test, or if new symptoms have arisen. For a child, a paediatric service may be most suitable to continue monitoring. For adults, a referral to a general physician with experience with hard to diagnose conditions may be suitable.

It’s often said people with a suspected but undiagnosed rare disease are on the ‘diagnostic odyssey’. This is because not having a diagnosis can be very challenging for people with the condition and their family. In the video below, Maria shares her story about living with an undiagnosed rare disease, including things she found helpful and unhelpful.

Some Other Things That May Be Helpful

Share Recommendation 2 of the National Recommendations for Rare Disease Health Care with Your Health Care Provider2

This recommendation provides guidance for health care professionals about how to support people suspected of having an undiagnosed rare disease and their families. You could discuss the recommendation with your doctor and use it to form a plan together.

Find Mental Health and Wellbeing Support

Living with an undiagnosed rare disease is often very stressful and isolating and many people find getting mental health and wellbeing support helpful. The Mental Health and Wellbeing Support for Australians Living with a Rare Disease page provides links to mental health and wellbeing resources for people living with rare undiagnosed diseases.

Seek Support from Others with Similar Experiences

People living with rare and undiagnosed diseases often feel isolated. Connecting with peers can be helpful.

Syndromes Without A Name (SWAN) Australia provides support to children with complex, rare, and undiagnosed genetic diseases and their families.

Genetic Alliance Australia provides support to both children and adults with rare and undiagnosed rare diseases and their families.

Acknowledgements

This resource has been co-designed by Rare Voices Australia’s (RVA) Scientific and Medical Advisory Committee and RVA Partners, Genetic Alliance Australia and Syndromes Without A Name (SWAN) Australia.

References

- Zurynski Y, Deverell M, Dalkeith T, et al. Australian children living with rare diseases: experiences of diagnosis and perceived consequences of diagnostic delays. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2017;12:68

- Rare Disease Awareness, Education, Support and Training (RArEST) Project. National Recommendations for Rare Disease Health Care (2024). Available from: https://www.rarevoices.org.au/national-recommendations

- Whelan AJ, Ball S, Best L, et al. Genetic red flags: clues to thinking genetically in primary care practice. Prim Care 2004;31:497-508